Author: Fabian Kröger. Published on October 7, 2006 on Telepolis.

“Designers used to be servants in car companies, today they are kings,” says [1] one of these kings: Patrick Le Quément is head of design at Renault, which was the first car company to establish the post of head of design. As the quality of cars has improved and they become more similar, aesthetic criteria have gained enormously in importance over the last 15 years. Today, it is not the functional but the symbolic-social utility value of a car that is the primary incentive to buy it.

However, it is not the unique imaginative power of a designer that manifests itself in design, but a certain cultural habitus. With Bourdieu, car design can also be described as a “social order that has become a body”. It is a mirror of people’s bodily dreams. What the cultural scientist Hartmut Böhme writes about the human relationship to animals[2] also applies in an astonishing way to our relationship with the automobile: they are not only objects of utility, the human relationship to them also makes them “objects of desire, projection, exchange and feelings.” The closeness and intensity of the human-animal relationship thus finds its modern equivalent in the human relationship to the car.

Car design has always borrowed from people, animals or other means of transport such as airplanes or ships. A tour of the Salon d’Automobile in Paris, which opened last weekend, reveals that the car today is increasingly pushing to transcend the boundaries of its species; it tends to mutate, to become an animated hybrid, obeying a demonic look. This can be seen most clearly at this year’s Salon d’Automobile in the numerous concept cars, whose design often embody the purest form of automotive phantasms. The hybridization of heterogeneous animal and human elements in automobile design leads to a similar embodiment of divine and demonic powers as in the mythical creatures of antiquity.

Renault’s seductive flying god-like fish

In order to emphasize the deliberately mythical character of their products, automotive companies like to draw on the ancient myths of the Greek and Roman gods: Volkswagen recently presented the Eos convertible, named after the winged Greek goddess of dawn [3]. She is the sister of the sun god Helios, after whose son, who fell from the sky, the brand strategists had already named their luxury saloon Phaeton a few years earlier.

With the Nepta concept study, inspired by Neptune, the Roman god of the sea, Renault now also wants to generate atmospheric and real added value: After all, the automobile is “a mythical object that must be cared for. There is a danger that the car will become an arbitrary product,” worries Patrick Le Quément from Renault. To counteract this impending profanation, Renault designers launched the “seduction” phase back in 2003 (see interview with Le Quément in form magazine 1/2003). This is made very clear by the exterior mirrors [4] of the Nepta, which hang out of the car next to the windscreen “like ripe fruit on two thin branches”. Whether this allusion to the fall of man is also well received by potential customers is another question: users of a car forum [5] believe that they only recognize profane “street lamps” in the unconventional shape.

A techno-zoomorphic cross between a boat and a butterfly

With the bodywork based on the shape of a boat, Renault harks back to the first means of transportation ever invented. The front of the concept car describes a bow shape, the undulating side line slopes gently towards the rear and ends in a long overhanging, tapering stern, reminiscent of noble motorboats such as the legendary Riva. This flowing wave shape embodies a design turnaround that began in 2004 with the Fluence [6] study and will be seen for the first time in a production vehicle next year in the Laguna [7] model. This is intended to replace the previously common stubby rear aesthetic – which brought the Renault Mégane’s “duck ass” into the German feuilleton [8] in 2003.

A car that is shaped like a boat is saying: my origins lie in the water, I have sprung from another form. The designers seem to have derived the electrically controlled gullwing doors of the convertible from the metamorphosis of a butterfly paired with a flying fish. It is not actually a door, but half of the bodywork that folds up towards the middle like a butterfly to reveal the seats and engine. A small scratch in the side should therefore make it necessary to replace half the car. Deep underground garages could also require a courageous pike over the side edge – perhaps the first sports car that also requires a sporty driver. To dispel such profane doubts, the doors are equipped with an electronic obstacle detection system and anti-trap protection.

Failed luxury experiments

With the luxury-class Nepta convertible, Renault once again underlined its claim to return to the era of luxury saloons. In 1912, the fleet of the entire Russian court consisted only of Renaults. Before the Second World War, Renault built limousines such as the Reinastella model [9], in which the Président de la République drove up. With the nationalization after the war, the brand was assigned the small car division, Peugeot took over the mid-range and Citroën the luxury class.

In the mid-1990s, Renault picked up the luxury car tradition again and presented the spacious Initiale concept car for the first time at the IAA in 1996. Just two years later, the prototype of today’s VelSatis was shown at the Paris Motor Show and had been in production since 2002. Renault originally wanted to sell 20,000 units of the chunky luxury saloon across Europe in the first two years of production – but only a third of this target was achieved. The model remained largely unknown outside of France. An even greater disaster occurred at the same time with the production of the Avantime, which started in 2001. Its production was discontinued in May 2003 after only 8,545 Avantime were sold, of which around 800 were sold in Germany. The experiment to return to the luxury car class thus failed. Studies such as the Nepta therefore initially have little chance of going into series production and are primarily used for marketing purposes.

The birth of design from the spirit of ritual

The design also includes the question of the human-machine interfaces in the car. The cockpit of the Nepta consists of a spartan arrangement of integrated digital and analog instruments. With the return to clearly arranged instruments, the engineers want to overcome the attention delirium in the cockpit of modern cars (see Risky multitasking [10]). “Touch Design” is what Renault calls the aim of making the meaning of all controls ‘intuitive’. “We want to demystify technology. We want technology to serve people and not the other way around,” says Le Quément.

In the words of philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, Renault is merely igniting a new level of mystification: The “principle of design” only conceals the humiliation or embarrassment we feel when dealing with technical devices. Designers provide us with pleasurable competence in the face of obvious incompetence in dealing with devices whose complicated inner workings we cannot begin to understand. In this sense, the user is a charlatan to whom the designer, like a charlatan outfitter, gives the accessories for his “simulations of sovereignty”.

Even prehistoric man was constantly confronted with the fact that he was unable to influence certain (natural) events. However, as they were subject to the protection of certain cultural techniques – rituals – in such situations, they did not experience this as powerlessness in the face of their environment. To survive a storm, the weather god was invoked. “The gap through which powerlessness, panic and death enter life has been closed by rituals since archaic times.” Sloterdijk therefore speaks of the “birth of design from the spirit of ritual”; for him, design is a gesture of creating order; it is a kind of vade mecum against powerlessness in the face of an uncontrollable, permanently disintegrating and dissolving world. The moment of ritual conceals the disappearance and disintegration to which we are at the mercy of: Design is thus when, after a plane crash, the airline’s logo is quickly painted over alongside the rescue of the injured – as happened in the 1970s with a Swiss Air plane in Athens.

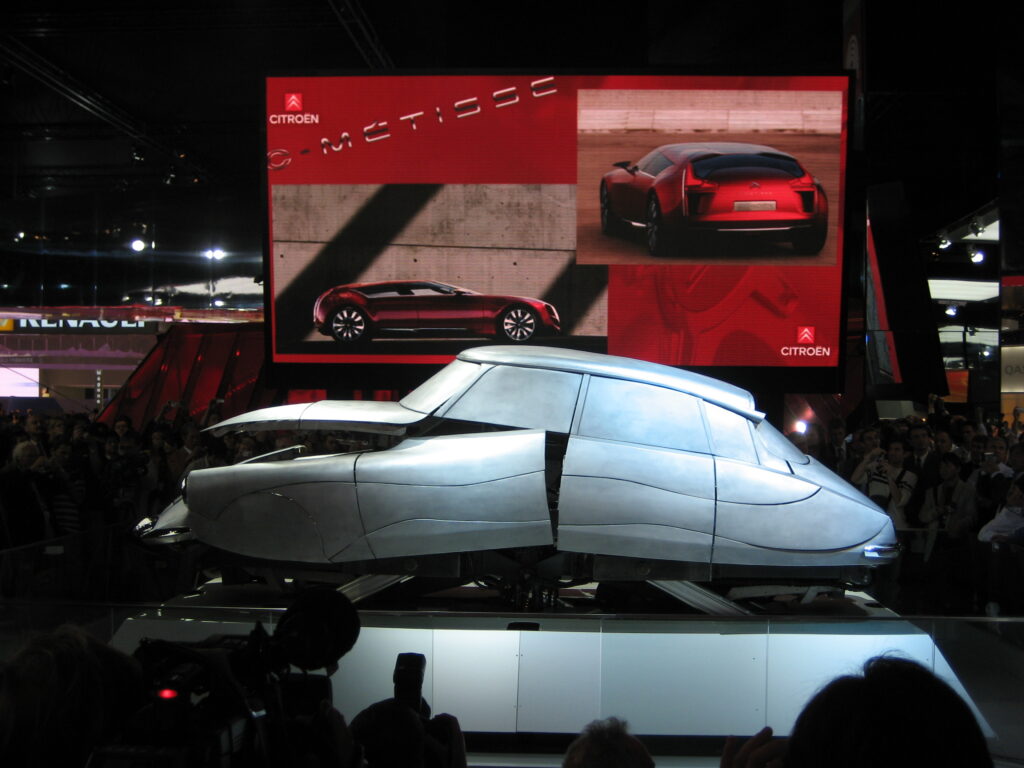

The Totem-Mobile mirrors Citroën’s pregnant half-breed

As design rituals must already comfort us from our Promethean shame, totem and taboo are not too far away: not far from the huge Renault exhibition site, Citroën has erected its diabolical black and red premises. Visitors are greeted by the shimmering silver body of a Citroën DS, which literally claims to be a “Déesse”, a goddess.

This installation by the New York artist Chico MacMurtrie and the artist group Amorphic Robot Works, founded in 1992, [11] called “Totem-Mobile” is truly self-mobile, i.e. auto-mobile: at the push of a button, the body unfolds towards the sky and points like a divine finger in the direction of the longings inscribed in all future studies with their wing doors and butterfly doors: Deus ex machina. In the form of the totem, the DS refers to the mythical origins of the brand and embodies the fundamental taboo of the automotive industry that must be respected: the essence of automotive longings always remains the desire for divine omnimobility, detachment from earthen constraints, transcendence.

The neighboring Métisse design study also pays homage to the aura of this totem. The name means “half-blood” and alludes to the diesel-hybrid technology of the sports coupé, which Citroën intends to bring to series production by 2010. Perhaps hybrid cars are more readily accepted than purely electric vehicles because they do not completely lose the aspect of taking something in and leaving something out, which is so important for the vitalization of the automobile. However, as alternative drive concepts are not particularly sexy, they also need spectacular design to attract the desired attention.

Five meters long, two meters wide and just 1.24 meters high, the gullwing looks like something straight out of a science fiction film. Everything about this study huddled against the ground points towards the heavens: the front wing doors with their vertical transfer movement indicate the desire to open the heavenly gate from the earth. They thus perfectly fulfill the theological mission sent out by the DS totem. By describing a spiral path, the rear doors refer to the divine spiral of DNA, also the object of human efforts for improvement. These symbolic allusions are complemented by tangible reminiscences of fighter bombers: there are greedy air vents in the front section and the starter button inside is housed in the roof console, just like on airplanes.

With its white bucket seats, the interior borrows from Chris Cunningham’s hypnotic music video for the Björk song All Is Full Of Love[12], which in 1999 showed the human-machine in the form of animated anthropomorphic robots that clone themselves in their own image. The round rear end refers to the pending birth of a new centaur – the driver fused with the machine – of which the futurist Marinetti was the first to rave. The design language of the Métisse is thus reminiscent of the fact that the automobile has long since extended the physical functions of the human body like a prosthesis and now also wants to participate in elementary events such as birth. The study thus completes the arc between man and machine, earth and sky.

Man is reflected in the evil eye of the big cat

In the third hybrid creature to be discussed here, the feline Peugeot study 908 RC, one might think one recognizes the monsters, mythical creatures and demons called gargouilles[13] on the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Just as the sacred church space of Notre Dame was to be protected from the intrusion of evil by holding Lucifer’s own ugly face against it, the “evil eye” of today’s automobile front sections is intended to ensure that the driver can continue on his way undisturbed. “Like a megalomaniac stag dreaming of being nothing but antlers at some point, the car design of the present day goes through all the imposing gestures of zoology,” wrote Ulrich Raulff two years ago in the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

In line with the brand emblem, it is the big game that inspired the design of the front end of the 908 RC. According to Peugeot, the extremely short overhanging front is “directly based on the head shape of a big cat”, but could have come from a small car and therefore clashes with the enormous length of the vehicle. The cockpit, borrowed from an airplane, is positioned extremely far forward and is arched over by a huge windscreen that extends beyond the driver and merges into a glass roof. A kink in the A-pillar destroys the smooth roofline approaching from behind, which appears to have been borrowed from a chopped VW Phaeton saloon. This ride through the type classes ends in the clapped-on rear end of a sports car, flanked at the sides by swollen cheeks with huge 21-inch alloy wheels. Overall, the study looks like an unbalanced clownish cross between three completely different vehicle types without any adaptation of the transitions.

More interesting are the claw-like chrome drops in the rear lights, which echo the feline predator motif at the rear. The tearing claw at the rear of the Peugeot dispels any remaining doubts: here, man has taken possession of the dragon, domesticated it in order to harness it for his own purposes. From a psychoanalytical point of view, the dragon is a container in which the outside of civilization is imagined, writes cultural scientist Hartmut Böhme. The aggressive and destructive desires of our own culture are externalized in this fantastic hybrid creature in order to be able to distance oneself from this violence. Böhme provides the key to understanding the concept cars: he writes that the decisive factor in the monsters is a drive dynamic that comes to the fore in their physiognomic expression: In the demons’ angry grimaces, the threatening savagery of man himself – sexual and oral greed and aggression – is depicted.

All in all, it becomes clear that the Paris Motor Show is an intermediate realm populated by beings that owe their existence to the metamorphotic exchange between humans, gods and animals. This realm, to which animals and monsters as well as humans had to lend their physiognomy, was created in order to conceal the fact that from all the figurations and grimaces of demonic front sections, only man himself ever looks out at us: The monstrous automotive hybrid embodies an extreme form of human self-encounter.

Links

[1] http://evenements.caradisiac.com/salon-paris/Nepta-un-eloge-au-mythe-automobile-542

[2]http://www.culture.hu-berlin.de/hb/volltexte/texte/zwischenreich.html

[3]http://www.griechische-antike.de/gott-goetter-helden.php/E/

[4]http://www.manager-magazin.de/life/auto/0,2828,437264,00.html

[5]http://www.motor-talk.de/showthread.php?s=96724f8276f050c81d8bb3eb1abcbac3&forumid=208&postid=10190863#post10190863

[6]http://www.prova.de/archiv/2004/00-artikel/0085-renault-fluence/index.shtml

[7]http://www.auto-motor-und-sport.de/news/erlkoenige/renault_laguna.85952.htm

[8]http://zeus.zeit.de/text/2003/40/Autotest_40

[9]http://www.leblogauto.com/2006/03/renault_sengage.html

[10]http://www.heise.de/tp/artikel/14/14064/1.html

[11]http://amorphicrobotworks.org/car/index.html

[12]http://www.glassworks.co.uk/search_archive/jobs/bjork_all/

[13]http://ndparis.free.fr/notredamedeparis/menus/paris_notredame_gargouilles.html